I.

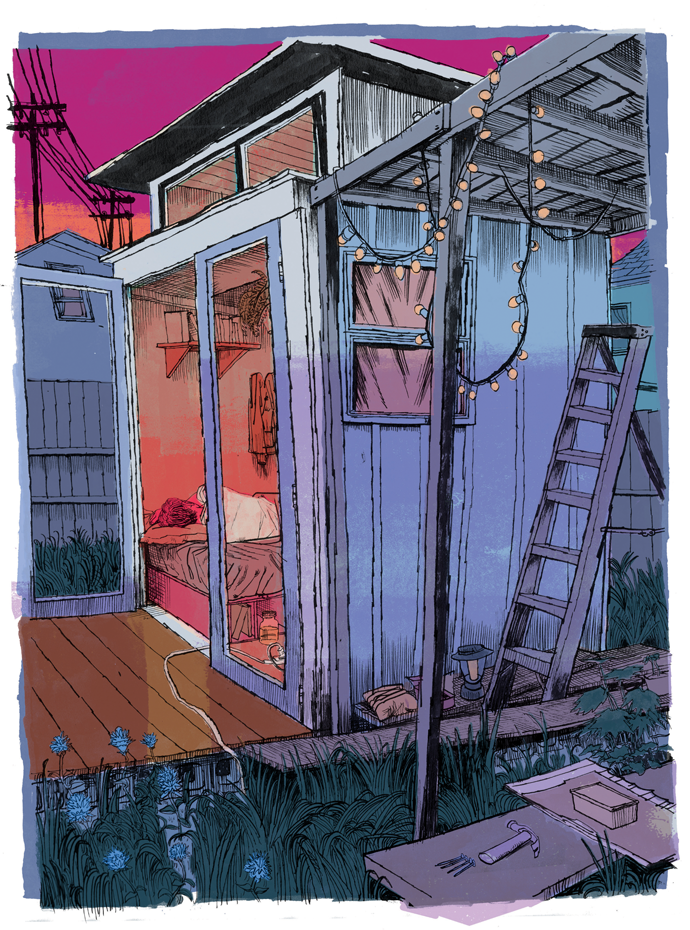

That year, the year of the Ghost Ship fire, I lived in a shack. I’d found the place just as September’s Indian summer was giving way to a wet October. There was no plumbing or running water to wash my hands or brush my teeth before sleep. Electricity came from an extension cord that snaked through a yard of coyote mint and monkey flower and up into a hole I’d drilled in my floorboards. The structure was smaller than a cell at San Quentin—a tiny house or a huge coffin, depending on how you looked at it—four by eight and ten feet tall, so cramped it fit little but a mattress, my suit jackets and ties, a space heater, some novels, and the mason jar I peed in.

The exterior of my hermitage was washed the color of runny egg yolk. Two redwood French doors with plexiglass windows hung cockeyed from creaky hinges at the entrance, and a combination lock provided meager security against intruders. White beadboard capped the roof, its brim shading a front porch set on cinder blocks.

Illustrations by Matt Rota

After living on the East Coast for eight years, I’d recently left New York City to take a job at an investigative reporting magazine in San Francisco. If it seems odd that I was a fully employed editor who lived in a thirty-two-square-foot shack, that’s precisely the point: my situation was evidence of how distorted the Bay Area housing market had become, the brutality inflicted upon the poor now trickling up to everyone but the super-rich. The problem was nationwide, although, as Californians tend to do, they’d taken this trend to an extreme. Across the state, a quarter of all apartment dwellers spent half of their incomes on rent. Nearly half of the country’s unsheltered homeless population lived in California, even while the state had the highest concentration of billionaires in the nation. In the Bay Area, including West Oakland, where my shack was located, the crisis was most acute. Tent cities had sprung up along the sidewalks, swarming with capitalism’s refugees. Telegraph, Mission, Market, Grant: every bridge and overpass had become someone’s roof.

Down these same streets, tourists scuttered along on Segways and techies surfed the hills on motorized longboards, transformed by their wealth into children, just as the sidewalk kids in cardboard boxes on Haight or in People’s Park aged overnight into decrepit adults, the former racing toward the future, the latter drifting away from it.

To my mother and girlfriend back East, the “shack situation” was a problem to be solved. “Can we help you find another place?” “Can you just find roommates and live in a house?” But the shack was the solution, not the problem.

As penance for abandoning my girlfriend, I still paid part of our rent in New York, and after covering my portion of our bills, my student loan payment, and car insurance, I had about $1,500 left over each month. That wouldn’t have been so little to live on, except that, according to some estimates, apartments then averaged $3,500 a month in San Francisco, $3,000 in Oakland. That year, 2016, 83,733 low-income San Franciscans would apply for the city’s affordable housing lottery, fighting for 1,025 slots. There were still cheap rooms available in the Bay, to be sure, mostly in ramshackle Victorians or weathered Maybeck bungalows where artists or activists or punks lived collectively and were protected by rent control, but these rooms were in dwindling supply and astonishingly high demand. On Craigslist or by word of mouth, vacancies were often offered exclusively to “Q.T.P.O.C.” (queer and trans people of color) or “B.A.B.R.” (Bay Area born and raised) roommates, a reasonable defensive measure against the ravages of the tech economy, which, block by block, was replacing the weird old counterculture with Stanford M.B.A.s and Google engineers.

For those of us caught in the middle, it meant that to score a bed, you had to have Q.T.P.O.C. friends willing to make an exception for you, or be a member of obscure Facebook groups like (<O>’’’<O>), which served as an underground network for people seeking shared housing. (The page also offered bartered services like massage and childcare and, on at least one occasion, a “free hearse.”) As in other cities under intense economic pressure, marginalized inhabitants had created an alternate, black-market rental economy: the currency may have been cultural capital, but competition was still fierce.

I spent a few weeks on friends’ couches before an acquaintance posted on Facebook about a room opening in his eight-bedroom house in Oakland for $475, a steal, and I messaged him immediately. Thirty people had already written, he said, and his roommates had also received scores of inquiries, so the odds weren’t good. He stopped answering my emails after that. The same thing happened with a few vacant rooms I tracked down at illegal warehouses, cavernous lofts where residents scrimped on such things as functioning plumbing or reliable electricity in order to have space to paint and make sculptures and host bands all night, places like the Dildo Factory, or Heco’s, or Ghost Ship, whose leaseholder posted a roommate-wanted ad on Craigslist that winter seeking

all shamanic rattlesnake sexy jungle jazz hobo gunslingers looking for a space to house gear, use studio, develop next level Shaolin discipline after driving your taxi cab late at night, build fusion earth home bomb bunker spelunker shelters, and plant herbaceous colonies in the open sun & air.

I didn’t answer the Ghost Ship ad, but I went to a few “auditions” at other lofts. There were so many people vying for the spaces, I rarely got a call back and was never offered a room. I’d squandered whatever cool I once possessed, it turned out, by building a “normie” career as a writer and editor on the East Coast.

Growing up in rural upstate New York, raised on food stamps and free school lunches, my dad off to prison for a spell, I never met anyone who made a living in publishing. But in 2007 I was accepted into U.C. Berkeley’s graduate program in journalism. I saw the school, and the scholarship it offered, as a possible entrée to a world I had believed wasn’t available to working-class people like me. So, at age twenty-five, I stuffed my Toyota Camry with books and clothes, and, accompanied by my then girlfriend and $500 in savings, I drove west to a state I’d never even visited, hoping Cormac McCarthy was right when he wrote, in No Country for Old Men, that the “best way to live in California is to be from somewheres else.”

The Great Recession had not yet hit, and cheap housing was easy enough to find, even for someone with no credit or bank account. When my girlfriend and I broke up, I landed at a ratty mansion, Fort Awesome, in South Berkeley. My rent for one of the mansion’s eleven bedrooms was about $300 a month. There was an outdoor kitchen the size of a large cottage, three guest shacks, and a wood-fired hot tub built from a redwood wine vat. About thirty people lived on the compound, including a few children. The adult residents were a mix of hippies, crusties, anarchists, outcast techies, chemistry grad students, addicts, and activists—a cohort that shouldn’t have lasted a day, but in fact had lasted six years, ever since some of the residents had banded together and, with the help of a community land trust, bought the plot for $600,000. (Today, the property is worth about $4 million.)

I was unwittingly among the vanguard of a wave of gentrification—a transient “creative” living in a “rough” neighborhood not yet fully colonized by the white middle class—and sometimes it was tense. I almost brawled one night with three teens who shoved me out front of a liquor store; another night I fought off a mugger and came home with a black eye. But otherwise the Bay was astonishingly convivial—for the first time in Oakland’s history, the city’s populations of African-American, Latino, Asian, and white residents were almost exactly equal in size—and I fell in love with dozens of squats, warehouses, galleries, and underground bars, where black hyphy kids and white gutter punks and queer Asian ravers all hung out and partied together, paving the way for later spaces like Ghost Ship. It felt like the perfect time to be there, like I imagined the Eighties on New York City’s Lower East Side.

Some of the wildest parties took place at a landfill. Since the 1960s, the city of Albany—immediately north of Berkeley—had been dumping industrial waste on its shoreline, creating a thirty-three-acre peninsula of debris that jutted out into the Bay like the toe of Italy’s boot. In the 1990s, cops began encouraging the homeless to settle on this abandoned stretch of land, and others soon joined them to take advantage of the nigh-lawless space. Bands brought generators and had shows, skaters built a concrete half-pipe, sculptors pieced together giant monsters and mermaids from rebar and glass that had washed ashore. A little squatter village thrived on the beach, where folks lived in shanties crafted from flotsam—they had even built a little lending library.

One of my roommates at Fort Awesome, Andy, built a shack out at the landfill, and the old-school home-bums more or less accepted him. Some nights I would ride my bike up to Albany and drink with Andy’s new neighbor, Jimbo, a metal scrapper who lived in a hundred-square-foot hovel built from packing pallets and driftwood. Jimbo let me hang out if I brought him batteries for his FM radio, and we’d sit sharing Miller and Mad Dog, listening to KPFA, gazing out his one window at a beautiful panorama of the Golden Gate Bridge and the Marin Headlands twinkling on the far side of the bay. It would’ve been a $10 million property if it hadn’t been built atop a toxic trash dump, but the trash was the only reason anyone let Jimbo make the space his own in the first place, so he accepted the trade-off as the cost of admission to paradise.*

The landfill was where I first met Jenny. A band of musicians clutching harmoniums and ukuleles jammed in a crabgrass clearing at midnight. Nettle tea was ladled from an oil drum and 40s of malt liquor were passed around. Someone strung paper lanterns between the palm trees. Jenny—black bangs and homemade tattoos on her hands—lugged a wicker picnic basket through the grass. She wore a sparking silver dress, like a space suit, with a black cardigan over black jeans and black clogs, and she walked with a limp.

She told me she’d had a miscarriage earlier that week. “On purpose,” she said, a procedure she’d performed with some concoction of herbs. Why tell me, I wondered, a stranger? Taking me into her confidence only hastened the crush I already had on her, but on this night we just talked and shared weed brownies, and at night’s end I accidentally rode my bike off a trail and crashed into some dogwood brush littered with heroin needles.

Now, eight years later, in 2016, I was back in Oakland for my new job. After nearly a month of looking for a place to live, I got a text from Jenny: “Would you consider a shack?”

An ex-boyfriend of hers had a disused shed in the backyard of his West Oakland home. Jenny worked as an artist and musician, but mostly as a barista, and she lived in a squalid garage nearby with her instruments and two cats, where she paid $500 per month. She was a victim of the housing crisis in her own way, and if she didn’t want the shack, I knew there must be a reason. It was smaller than a closet, she warned me, and illegal to inhabit, but if I was willing to seal it against the elements and finish construction, I could rent it for $240 per month. I said yes without even visiting.

Erik, Jenny’s ex, had built the shack as part of an attempt to start a tiny-house construction company, designed to shelter the ever-growing legions of homeless. In the years since I’d been gone, the second tech boom had arrived in the form of Uber and Twitter and hundreds of other startups, enticed north from Silicon Valley by tax incentives and backing from venture capitalists based in San Francisco. Hundreds of tech companies had moved or expanded into the city, and some 130,000 jobs had been created. But only about 15,000 new homes had been built, and the housing crunch and rising costs had sent thousands of people to Oakland and Berkeley, seeking cheaper rents and mortgages. Tech’s expansion into downtown Oakland was pushing out the middle class even farther, and threatening to destroy the fabric of working-class cities like Richmond and Vallejo.

The front line of gentrification in the East Bay had, in turn, moved from my old stomping grounds around Fort Awesome in South Berkeley to West MacArthur Boulevard, precisely where my shack was located, one of several remaining pockets of tension and crime near Oakland’s city center. Once again, chasing cheap rents, I had found myself on the barricades of cultural conflict, though now I was too old and wise to be ignorant about which side I was on, even if I was still too poor to do much about it.

Erik had hoped to sell his inexpensive tiny-house prototype to the cities of the Bay, which would produce them en masse and distribute them to the poor. (Oakland did eventually experiment with tiny-house villages, though they hired architecture firms to design them rather than an amateur like Erik. The venture houses less than 5 percent of the city’s homeless population.) Erik had gotten as far as building two prototypes in his backyard before the effort stalled, leaving one of the unfinished structures vacant for me.

The twin building, an identical shed overflowing with tools, rusty bike frames, and wood scraps, stood beside my shack. Between the two was a firepit where someone had spit-roasted a gym sock and where I sat some nights and drank beer. Along a fence was a chicken coop, home to a forlorn cock named Pepper who later that winter would be murdered by one of the dozen raccoons that haunted the abandoned house next door, which had just been sold to a couple of engineers at Google.

Inside, my hovel smelled musty as a summer cottage in the off-season. The walls were unpainted plywood. The floor, tongue-and-groove softwood, had never been stained, except by rain, which had leached through the boards, turning the fir underfoot a buttery brown. At eye level was a loft. It was intended as sleeping quarters, to maximize the square footage, but in fact it offered about as much space as an overhead bin on an economy flight. A treacherous ladder, built like a game of Jenga, led up to this compartment.

I’d brought only one small suitcase to California, and I stowed it in the loft. Below, I hung my dress shirts from a strand of twine. I nailed a scrap of wood to a wall, upon which I shelved a few novels, some candles, and my mason jar. I had pilfered a tattered twin mattress from the front house, and I laid it across the water-warped floor. The mattress carpeted the softwood nearly wall-to-wall, so that to dress I had to stand on my bed, and to lace my shoes I kicked open the French doors and stretched my feet into the yard.

It rained. First for days, then for weeks. The yard filled up with a quarter foot of water, as if somewhere a levee had collapsed, and the heads of coyote mint and monkey flower became lily pads. At night, ghosts of mist rose from the pools, and inside my shack I could see my breath, even with my space heater turned to ten. The power flickered. To use the toilet or kitchen in Erik’s house I dashed through the mud, high-stepping, and returned to the shack soaked and shivering. There was nowhere to sit or lie other than my mattress, so I spent most nights pupated in my sleeping bag, the zipper under my chin, the space heater tucked under the covers with me as I watched the rain fall outside and the waterline creep slowly up the walls.

When the clouds finally cleared, it made me glad for the rain, because without the storms I wouldn’t have been so ecstatic for the arrival of sunshine. The temperature climbed toward spring, the ground dried out. I could now make much-needed renovations to my shack. I asked Jenny to meet me at Home Depot with her Jeep.

To get there, I had to bike down West MacArthur Boulevard to San Pablo Avenue. Immediately beside the house were three motels—the Palms, Bay View, and Nights Inn—and the fine weather brought out the hustlers, pimps, and sex workers from inside their damp rooms to do their deals on the sidewalk. Sunlight, it turns out, is not the best disinfectant, not in Oakland anyway, and scummy condoms and dirty needles sprang up like flowers between the paving stones.

Across the street from my shack was Easy Liquor. A few weeks earlier, I’d been walking home in a downpour when I stumbled on a shirtless man circling its parking lot, shouting angrily, his hands clutched over his stomach. I asked if I could help. “Pull it out!” he shouted, and he shook his fists at me, revealing a knife handle where his belly button should have been. Another evening, on West MacArthur, I watched a large man shove his shopping cart into the path of a techie on a bicycle. The techie swerved and fell, and the homeless man put one foot on his victim’s chest and tugged at his Google laptop bag. “Help me!” the techie shouted as they played tug-of-war. I sprinted over and pushed the two men apart, yelling, “Get the fuck out of here and don’t come back!” I was talking to them both.

My neighbors’ homes were mostly blighted bungalows with peeling stucco, dust-bowl lawns, and barbed-wire fences. Men bench-pressed weights in driveways. Cars left on the street overnight would often appear the next morning with smashed windshields and cinder-block tires. The neighborhood’s boundaries were drawn by the “wrong” side of the BART train tracks and Telegraph Avenue to the east, bleak San Pablo Avenue to the west, and its southern and northern borders were marked by 35th Street and Ashby Avenue, beyond which were the newly bourgeois enclaves of Temescal and Emeryville. It wasn’t really a coherent neighborhood but its proximity to BART and the general scarcity of housing in the Bay had led developers to try to rebrand it “NOBE” (North Oakland Berkeley Emeryville), an absurd neologism I never once heard used except by real estate boosters.

Yet the rebranding was working, at least on paper. I seldom saw well-to-do white people on the streets, except when they were hurrying home or being mugged, but two- and three-bedroom cottages in the neighborhood were going on the market for $1.5 million, $2 million, and sold for hundreds of thousands of dollars more, often bought in cash by coders or executives who’d come east from San Francisco or west from the eastern seaboard to work for LinkedIn or Twitter or Atlassian or Oracle. As soon as a for sale sign went down, the ghetto bungalow behind it would be remodeled, landscaped, and encircled by a steel gate. The new inhabitants would only appear in public twice a day. In the morning, the jaws of their gated driveways opened, spitting tasteless Teslas and BMWs out into the streets, their drivers racing past the Palms, the Bay View, the Nights Inn, and Easy Liquor en route to the freeway or BART’s police-patrolled parking lot. At night, their gates would open to swallow them again, so they might sleep safely in the bellies of the beasts they called home, safe from the chaos outside.

At the end of our block was a monument to the housing wars: an eight-story, 105-unit, half-completed condo building that no one had ever lived in, and that no one ever would, casting its Hindenburg-size shadow over my shack. Just before my return to California, and amid rumors of anti-gentrification arsons, it mysteriously caught fire. This blaze devoured more than $35 million in labor and materials, and now the steel skeleton bowed and buckled. The entire top floor had collapsed, and the facade was seared with black smoke stains. (When someone torched this same building again several months later, police decided definitively that it was arson. I recall riding through the smoke on my bike that day.) As a result, the funders, Holliday Development, had ringed the property’s perimeter with chain-link and posted a twenty-four-hour armed sentry in a little matchbox booth inside the fence, a fat, tired man who waved to me cheerily when I cycled by.

Beside the half-destroyed condo complex was the 580 on-ramp to San Francisco. Clustered there on the highway’s margins was yet another of the city’s countless, nameless tent cities, a patchwork of a few dozen tarps and tents lit up at night by flaming oil drums. Beyond this homeless depot was Home Depot. I locked my bike outside the store and wandered the immaculate fluorescent-lit aisles. I bought four sheets of O.S.B. board, a box of three-inch drywall screws, and an armload of two-by-fours. Outside with my haul, I heard the loud thunk-thunk-thunk of E.D.M. and the squall of rubber tires skidding into the parking lot—Jenny’s Jeep, a crack down the center of the windshield like a busted smile, swerved into view and stopped in front of me, Jenny’s grinning face and tousled black hair framed by the rolled-down window.

“Check out this cute work outfit I bought,” she said, jumping out of the Jeep and modeling a pair of black thrift-store overalls.

“Portrait of an urban homesteader,” I said.

Jenny’s parents had fled communist China in the Seventies; she’d grown up on the edges of Silicon Valley, and she displayed that contradictory mix of New Age solipsism and self-abnegation that characterizes a certain stripe of millennial Californian. She obsessed over astrological charts, danced in an experimental electronica band, and fumed about the “non-monogamous” Peter Pans she dated, who always mistreated her—men like Erik who, according to Jenny, had taken advantage of the Bay’s laissez-faire dating attitudes to conceal his phobia of commitment.

“You know what Erik told me when we broke up?” Jenny said after we’d loaded her Jeep with my materials and bike and headed back toward the shack.

“Do I want to know?” I said.

“He said, ‘You’re like a mirror. You have no sense of self. So I feel like I’m dating myself. And I hate myself.’ ”

“I thought he was a narcissist,” I said. “Shouldn’t he love looking in the mirror?”

“You’d think so.” She turned to me and sighed. “He’s an asshole.”

We jokingly called her parade of shitty boyfriends the “Lost Boys,” and neither Jenny nor I seemed to realize (or she was too kind to say) that in many ways I was one of them, wrestling with and resisting responsibility.

“I wish there was a better place for you to live,” Jenny said, as we drove past the devastated husk of the burned condominium project and the little guard booth, then Easy Liquor, its parking lot full of men throwing dice. “You could stay with me.”

“I don’t think my girlfriend would be stoked on that arrangement,” I replied. And truth be told, I wouldn’t have been stoked either. Jenny’s garage was twice the cost of my shack, and hardly nicer, and I could only take so much astrology. Besides, over the course of the winter, the shack had grown on me, or I’d come to appreciate the independence it afforded. I was willing, at least for now, to trade space for freedom. And I was excited to renovate. “I wish there was a better place for you to live,” I said.

“Yeah,” Jenny said. “Me too.”

At the shack, Erik helped me and Jenny unload the Jeep. Prematurely bald, with a halo of wiry hair and bushy blond eyebrows, and a daily uniform of ragged Carhartts, flannel, and pink Crocs, he cut the perfect image of the punky Lost Boy we described him as behind his back. He had sad blue eyes, clouded red from smoking weed, and he’d cultivated a hangdog bitterness about the foundering of his tiny-house company, even though by his own admission its difficulties were the result of his ambivalence, just as he’d bungled his relationship with Jenny who, because she had liked him, he’d resented for being a bad judge of character until she gained back his respect by rejecting him.

Now, a year after their falling-out, and even longer since he’d abandoned his ambitions of housing the homeless, he and Jenny had reconciled, though he hadn’t reconciled himself to the failure of his humanitarian scheme. As a constant reminder of this open wound, he frequently referred to my quarters as “the tiny-house prototype,” which seemed a bit grandiloquent to me, offensively so, because actually inhabiting his failed dream, as I did daily, felt more like living in a hobo’s nightmare: draughts whistled through cracks in the jambless French doors; weeds had sprouted up between the floorboards, tall as sunflowers; moisture perspired down the uninsulated walls; a fearless skunk squatted in the crawl space beneath the porch, perfuming my dress shirts with feral musk. When I called it “the shack,” Erik shot me a hurt, suspicious glare, blinking his bloodshot eyes, as if my description had been meant to underscore his failures. And yet, as easily as he could be cold, Erik could also be kind and thoughtful, lending me labor and tools, reimbursing me for building supplies and, on one occasion, lowering my rent $10 without my ever asking.

That evening, the Pacific breeze carrying the scent of jasmine through the streets of West Oakland, Jenny wandered off to pick chokecherries while Erik and I set about deconstructing the shack’s face. We unhinged the French doors. We placed new walls Erik had framed out on top of the four-by-eight porch and nailed them in place. Basically, we were adding another room onto my shack by turning the porch into an interior space, connecting it to the existing structure and attaching a corrugated metal roof. It was simple work, but I felt competent, capable, proud to craft something with my hands.

The rehab took most of the afternoon and evening, and the results looked good, sturdy enough to withstand a storm wind or a light seismic shuffle. In celebration, Erik sparked a spliff, I popped open a beer, and Jenny hung from the French doors a primitive wreath she’d woven, “a pagan ritual,” she said, “to keep bad spirits away.” She shrugged at me. “Unless you invite them in.”

It was still hardly anything most people would consider a home, but it was becoming mine through adaptation. Of course, it was illegal to live in a structure like this even in progressive-minded Oakland—backyard “in-law” dwellings in Alameda and San Francisco Counties mandate electricity and plumbing, and are required to meet basic building codes we’d ignored—and its illegality all but guaranteed that one day it would be taken away from me. But in the meantime, I could do anything I wanted with it, shaping semi-squalor into opportunity.

Living in the shack, I came to realize that part of my motivation in moving back to the Bay Area was an urge to return to my younger self, a desire for freedom from the pressures of adulthood. After grad school at Berkeley, I’d gone to New York City, wanting to be a writer—but there weren’t, and aren’t, really full-time jobs for writers, not the kind I wanted to be, anyway. So I chose to become an editor, which seemed to be a way to split the difference between the precarity of the artist and the banality of the white-collar wage slave. But my role in the middle class was by no means secure or guaranteed no matter how hard I worked, and I had come to feel deceived by the mirage of upward mobility: after almost a decade of uninterrupted employment, of doing everything “right,” I owned no property, I had no stocks, no investments, no wealth, no inheritance, no safety net or support system beyond a few thousand dollars in my savings account. One disaster—being fired, sustaining a serious injury, needing to help out a desperate friend—could wipe me out, and if that happened, what would I have gained in a decade as an editor? I had decided I no longer cared about ever becoming middle-class; the cost of earning a living this way was too high. The terror of poverty had become far less frightening than the wages of having wasted my life.

“It is a feeling of relief, almost of pleasure, at knowing yourself at last genuinely down and out,” George Orwell wrote in Down and Out in Paris and London. “You have talked so often of going to the dogs—and well, here are the dogs, and you have reached them, and you can stand it. It takes off a lot of anxiety.”

Standing in the yard that evening, bright stars overhead and dry grass underfoot, I marveled at the renovated structure: with relatively minimal effort, Erik and I had transformed the entire psychogeography of my home, and as a result my mental map was already reordering itself. The shack was still just 64 square feet, but my quarters had doubled in size. I imagined the desk I could now fit inside, and the chair, and a small dresser, and not having to use the yard as my changing room, and what more really did I need?

The powerful thing about smallness, it occurred to me, isn’t actually smallness for its own sake—the point, instead, is a matter of scale. If you reduce the size of your life enough, then the smallest change can be a profound improvement. Yet the hardest thing is to recognize your smallness without being diminished by it. In my shack I was always balancing that tension—I didn’t want to become so small that I disappeared, I just wanted to hide for a little while.

II.

The night Ghost Ship burned—December 2, 2016—I was out of town. Headlines about the disaster appeared in every major newspaper: “‘expecting the worst’ after deadly fire at party in oakland warehouse.” Photos showed an industrial building that could’ve been a storage facility or a private jet hangar, but for the decorative skulls, disembodied eyeballs, and the words ghost ship graffitied on the facade, which gave it away as a subcultural refuge. It was located just a few miles from my shack, in Fruitvale, across the highway in East Oakland. A friend of Jenny’s had organized the show that night. In the photos documenting the aftermath of the tragedy, the roof is a gaping black absence, eaten by flame, collapsed in on itself. The walls stand but are charred and crumbling in places. Debris lines the sidewalk. Fire trucks form a cordon. The bicycle of a partygoer sits chained eternally to a telephone pole. Inside the building, we now know, are thirty-six corpses.

Police and investigators have pieced together most of what transpired, if not the exact cause: Likely a small electrical shortage sparked a flame on the first floor of the warehouse, which quickly spread, undetected by attendees of the concert held on the second floor; the power and lights went out. To escape the mazy interior, some people jumped out windows, or climbed out onto power lines. Within three minutes, smoke filled the entire building. One victim texted his girlfriend his last words: “Fire. I Love You.”

The magazine where I was working had sent me to North Dakota that week, to write about the pipeline protests at the Standing Rock Indian Reservation, so I was on the prairie in a blizzard. I didn’t hear about the fire until the next morning, when all of the bodies hadn’t yet been counted, hadn’t yet been discovered, and I didn’t realize then how many of my friends and acquaintances were involved. Trolls on 4chan, drunk with glee from Donald Trump’s presidential victory, gloated about Ghost Ship, promising to notify authorities in other cities of illegal underground venues, “open hotbeds of liberal radical ideas and degeneracy.”

Jenny, meanwhile, wasn’t answering my texts.

Flights out of North Dakota were grounded, so I set out driving into the storm. The mountain pass west over the Dakota hills was closed, so I skirted a police line onto a back road. I didn’t see another car for six hours. The route was entirely erased by white, indistinguishable from the plains, the flurries so dense I could barely see beyond my rented S.U.V.’s headlights. I made it as far as Utah before a stalagmite of ice tore a hole through the gas tank. I got a tow, then a train the rest of the way back to Oakland.

A few days passed before I saw Jenny. I was walking down San Pablo Avenue near Home Depot when she drove by and honked. She pulled over. Her chin hung on her chest in exhaustion, blue bags underscoring her eyes. She was alive but looked ill. Several of her friends had died in the fire, as well as an ex-boyfriend, a Lost Boy named Billy.

In the days since, she’d been frantic—collecting donations for survivors, going to vigils, making phone calls to the friends of the dead in other states. On Facebook, someone erroneously accused her of stealing the donations. Not long after, a close friend of her family was murdered, and her grandfather suddenly died. She went to Taiwan for the funeral, and she was just now driving home from the airport after a sixteen-hour flight back. That’s why she hadn’t texted me. Her suitcase was on the passenger seat. “I’m so tired,” she said, “but I don’t want to go home.”

“I was gonna go get drunk alone,” I said, “because I don’t want to sit in my shack and stare at the wall.”

“Let’s go somewhere,” she said.

“Somewhere with beer,” I said.

“Somewhere with liquor,” she said.

We went to a dimly lit cocktails and tapas place where Jenny couldn’t afford anything. It bustled with blissfully unaffected engineers, coders, and lawyers, which I think is why Jenny chose it—there were no reminders of the fire, no friends, no survivors. Her hands trembled as she explained what had happened on December 2—how her band had wanted to play Ghost Ship that night, but they were already booked ten blocks away, at another underground venue called the Space Station, which is where they were when the fire began. She told me about the eerie coincidence of it all—about how she wore a handmade “death mask” while performing. About how Isobel, the band’s singer, had sung about fire—“What does burning mean when you haven’t lived in heat?”—exactly at the moment the Ghost Ship fire broke out. About how their smoke machine had set off the fire alarm, and they’d all laughed and kept on playing, unaware, like most people, of what was happening across town. (I have a cell-phone video shot by a partygoer at the Space Station that night: Jenny dances at the center of the crowd, wearing her papier-mâché skull. Smoke suddenly billows into the room. The fire alarm wails. It’s an unsettling premonition of the fire, a sort of alternate universe mirroring Ghost Ship just as it was burning down less than a mile away.)

I admitted it was a terrifying coincidence. But Jenny thought there was a deeper meaning, something darkly cosmic, and she explained that her life depended on decoding the connection. “It’s like, did we do some sort of rain dance?” she said over gin and tonics. “Did we cause the fire? Am I responsible?”

“You’re just trying to make sense of it,” I said, alarmed. Her pupils were huge saucers. I knew she’d had manic episodes before, and I wondered if that’s what this was.

“I’m scared,” she said.

“So am I.”

We left the bar. Downtown Oakland buzzed with that multicultural mix that still seems to me unique to the Bay, black and white and Latino teenagers, all stoned and drunk and stupid, but also wine bars and cocktail bars and bespoke restaurants and whistling panhandlers and glaring cops. We passed warehouses where we once went to shows—Kittenboat, Sugar Mountain, Ghost Town Gallery—all of which had since been emptied, turned into condos. In the year following the Ghost Ship fire, the nonprofit Safer D.I.Y. Spaces estimated that the city’s investigations of similar buildings led to the eviction of about eighty people—that many more added to the swelling population of homeless and displaced. Meanwhile, Oakland mayor Libby Schaaf exploited the tragedy by supporting laws streamlining the development process of condo projects, cynically claiming that they were a solution to the crisis exemplified by Ghost Ship because they created more housing—never mind that these condos were far out of reach of the bohemians who lived in places like Ghost Ship, much less the even more desperate folks, the truly impoverished, on the streets and in the tent cities.

This September, a trial for thirty-six counts of manslaughter against Ghost Ship’s leaseholder, Derick Almena—who wrote the ad seeking “shamanic rattlesnake sexy” roommates—and one of his subtenants, Max Harris, ended in an acquittal for Harris and a mistrial for Almena. Almena has been in jail for more than two years unable to make bail and will likely remain there until his retrial. Meanwhile, no one else has been charged—not the city inspectors who failed to gain access to the building only days before the fire, not the electrician who allegedly wired the faulty boxes, not the building owner who garnered $5,000 a month from her illegal tenants.

That night, Jenny had a breakdown, the details of which will remain mostly between us, except to say that she punched out a storefront window, a hailstorm of glass coming down on our heads, and we sprinted from the cops, and ducked into a bar, where Jenny collapsed on the dance floor, bleeding and sobbing and screaming that everyone was dead.

Eventually, I coaxed her into a Lyft. At the entrance to the backyard garage she lived in, I had to enter the padlock’s letter-code because her hands were too mangled and shaky: P-O-E-T. Inside, the room stank of stale cat piss and kitty litter. A mason jar beside her mattress sat nearly overflowing. Her garage had no bathroom, no kitchen, no heat, no water. She’d been living here for four years. We were both thirty-three, and I thought, This is utopia?

Collapsed on her threadbare mattress, Jenny snored loudly, the only sign she was alive. I recalled a painting of an abstract flame she’d had on her wall until recently, and noticed the empty spot on the cinder block where she must’ve taken it down, hidden it, thrown it out. I checked her pulse. She would be okay. Before staggering back to my shack, I put a trash can beside her and pulled the tattered covers up to her chin. Her hands were sticky with blood. Her leather boots, still laced tightly on her feet, poked out from the bottom of the comforter, as if, even now, she knew at any moment she might have to wake up from the dream and run for her life.

III.

Everyone was sick with sadness following the fire. I saw survivors at bars, their eyebrows singed off. I chatted with old pals at parties and realized they were talking about their girlfriends or boyfriends in the past tense, as if they were ghosts, because they were. There was talk of suicide, songs about suicide, attempts at suicide that failed and attempts that succeeded. Jenny cried every time we hung out.

In the end, I lived in the shack for eleven months. It shrank to the size of a cage. Living like an animal was no longer liberating. I grew tired of waking up in damp, soiled T-shirts. The weeds by my bed grew head-high. The skunk birthed a litter and left me. My mind a fog, I kept accidentally kicking over my pee jar. Living on so little had exacted a heavy toll.

Being down-and-out is cheap, sure, but the things you do to stand it become expensive, whether drink, drugs, or whatever other vice gets you through the night. Me, I started to sleep at fancy hotels, only as much as I could afford, or so I thought—once or twice a month at first, then three or four times, on payday weekends.

I told almost no one I did this. On a Saturday morning, I’d secretly ride BART into downtown San Francisco. I’d get off near my office. Aboveground, I’d call up the HotelTonight app on my phone. As guiltily as if I were ordering an escort, I’d book a room. Sunday morning, I’d climb back on BART with the plebeians, get off at West MacArthur, walk past the Palms, the Bay View, the Nights Inn, and return to the squalor of the shack, my skin moisturized and hair washed, stinking of complementary lavender-infused lotions and shampoos.

Deprivation breeds a schizophrenic, binge-and-purge mentality, and so, having begun to indulge, I indulged even further: I gave Erik notice I was leaving the shack and rented an apartment in North Beach, the old Beat neighborhood in San Francisco, not one of the city’s most expensive but certainly not its cheapest. I scrounged together enough for first and last on the cheapest place I could find—a not-at-all-cheap $2,600 a month studio at the top of Telegraph Hill—a luxury I knew I couldn’t afford, though I reasoned that if renting a nicer apartment prevented me from quitting my job for a little while longer, kept me from losing my salary and health insurance until I could line up another gig or grow the courage to finally give up on editing entirely, then I couldn’t afford not to upgrade my living situation.

Besides, I had fallen in love with San Francisco on my one-night jaunts at hotels throughout the city. I’d always preferred Oakland’s jagged grittiness to San Francisco’s old-fashioned, finger-snapping cool, but now I saw the city anew. Because the place was so expensive, I knew no one who lived there—virtually no colleagues, no fire survivors, no tears, no memories. I could be alone again. First in hotels, then in my little studio apartment, I experienced the city for the first time as a naïf, as Cormac McCarthy promised. Sure, the streets were still cracked up with poverty and inequality and chaos. But I came to respect San Francisco’s transparent presentation of the crisis afflicting it, which seemed far more honest, even if only accidentally, than what you see in most American cities, or, rather, what you don’t see, where the suffering of the underclass is hidden away and swept into ghettos and kept from spilling out by police and social workers and redlining mortgage lenders. In San Francisco, even more than in Oakland, the worlds of extreme wealth and extreme poverty cohabitated, and I felt most at home moving between them, accepting that my fate was to exist, economically and existentially, somewhere in the middle, even if the rich knew I was a scumbag and the homeless knew I was a yuppie.

Perhaps it was just my honeymoon joy at finally living in a proper little apartment, or finally putting some space between me and the dark clouds of Ghost Ship, but somehow, even with all the city’s stark economic tensions, it even seemed to me that people were nicer and happier in San Francisco than anywhere else in America. It’s possible that it seemed this way simply because I was happier and therefore nicer there, and so I attracted goodwill the way someone with a boyfriend or girlfriend is asked on more dates than someone who is single. How could I not be happy in a city that is possibly one of the most beautiful cities in the world, and certainly one of the most beautiful in America, where from the doorstep of my studio I could watch ships sail the Pacific, navigating Alcatraz and Angel islands, the Golden Gate Bridge; where wild parrots circled Coit Tower and coyotes yipped along the midnight paths and in the valleys were pasta shops and sidewalk cafés and taquerias and palm-tree parks; where you could walk from a bar to a beach in the time it takes to walk from Times Square to Penn Station, and you could bike over the Golden Gate into the redwood forest in the time it takes a taxi to stutter through the Holland Tunnel.

So, maybe everyone in San Francisco wasn’t actually nicer, they were just nicer to me, because I drew it out of them with my own geniality. And if this was true, that the city simply made me feel happier than I actually was, then you could apply that logic to other people as well: maybe the people of San Francisco weren’t nice people, so much as the beauty and charm of the city made them nicer simply because they were there in San Francisco, and this in turn made their peers around them nicer too. The effect, then, was a collective state of happiness that rippled from each individual to the next; a positive feedback loop of smiles and greetings and gratefulness to be there.

It took me just a few months to realize what a steaming load of shit all this was. The beauty and freedom and majesty of modern-day San Francisco was a fantasy glimpsed only from the vantage of my comfortable studio apartment, a fantasy propped up by my own mounting financial crisis, a fantasy I could believe only as long as I pretended I could afford the protections of my safe haven on Telegraph Hill, from which I, like all the other San Francisco renters and homeowners, was sheltered from the most brutal miseries and injustices the city inflicted on its army of homeless. Around that time, a computer technician had been kicking random street people in the face as they slept, killing at least one; the city’s good citizens voted by popular referendum to evict all the tent cities and bus the bums out of town, an effort foiled only by budgetary shortfalls (no one wanted to buy the bus tickets); partitions appeared on benches to discourage sleeping and residents raised $60,000 on GoFundMe to try to prevent the construction of a homeless shelter. In my case, I was finally forced back to reality by my credit-card debt: in less than six months in North Beach, I racked up $12,000 in charges trying to cover my bills and rent. The people of San Francisco weren’t happy. They were insane.

When I finally told my boss I was moving back East, I explained that the costs of sticking around, both personally and economically, were too great.

“That’s actually not so bad for San Francisco,” she said, when I told her what I paid in rent in North Beach.

“True,” I said, “it’s a pretty good deal. But it’s like sixty percent of my income.”

She winced. But she was a kind and sympathetic person, and agreed to let me try working remotely from New York.

On one of my last nights in California, I drank Millers and packed up my apartment: my books, my pee jar (which had been scrubbed and now held a bouquet of clarkias by the bay window), my saws and drills and the anti-Trump posters that had once decorated the walls of my yolk-yellow shack. I finished my last beer and smashed the bottle on the floor. I took a big blue IKEA duffel bag and stuffed it with as many of my possessions as would fit: two pillows, five pairs of socks, a hat, a sweatshirt, an unopened jar of peanut butter, a quarter-full jug of tequila. I wandered down the hill toward Washington Square. It didn’t take long to find someone. He was curled up in a doorway. I dropped the IKEA bag beside him. He blinked at me. As I stumbled back up the hill, he called out, “I won’t forget you, man.”

“It’s nothing,” I said, but, really, it was everything, or almost everything.

I pushed through the front door of my studio. I walked through the broken glass. I lay down on the floor with my shoes on. I balled up my jacket and put it under my head. I couldn’t sleep.